Inclusive Engagement Empowers Full Body Well-being

By Adrienne Cole Johnson, Maya Rockeymoore, Monica Chambers and Duron Chavis

Published in the Richmond Times-Dispatch on February 11, 2017

Nothing grows in trauma ...

When residents are relatively secure in the knowledge they are safe from harm and that their well-being is affirmed by a non-toxic environment, they are better able to broadly focus on building the skills, assets, and social ties that will sustain a lifetime.

Neighborhoods are the heart of any city and healthy childhood experiences are vital for promoting healthy adults. This is why we lovingly reflect the words of Frederick Douglass so often: “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

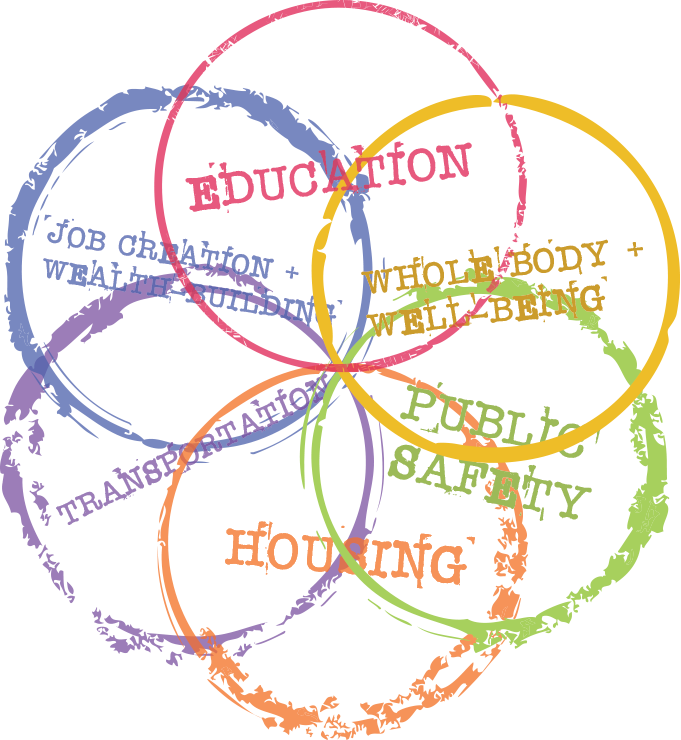

Whole body well-being is our attempt to look into what we are and what we become as individual citizens in this what we call “Community.” We suggest whole body as the collective mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional presence of entities that share in humanity. We further suggest well-being as the condition that provides for continued creativity, evolution, and expansion of life.

***

Preventable injuries, such as motor vehicle injuries, homicides, and suicides, are the leading cause of death among youth — especially youth of color — in the United States. Although not immediately life-ending, asthma, obesity, substance abuse, and poor self-image are a few of the notable conditions that contribute to health disparities among youth living in disadvantaged circumstances, disparities that often follow them into adulthood and ultimately undermine the quality and length of their lives.

On top of all of these factors, city, town, and school officials inadvertently intensify the disadvantage experienced by children by adopting policies and condoning practices that make youth feel unwelcome and ostracized in environments where they are supposed to feel as if they belong. Curfews, expulsions, negative interactions with authority figures, imprisonment, and inequitable budgeting for or the denial of important amenities and services are the most visible indicators of the deep malaise affecting children in schools and neighborhoods in lower-income areas.

Toxic stress is often the unrecognized and undiagnosed state of being for children and youth experiencing these disadvantaged circumstances. And yes, toxic stress results in a lifetime of negative consequences that undermine health and well-being.

Racism is a human phenomenon that permeates our social ecosystem. We tend to consider pollutants to our physical ecosystem to be of high levels of concern, particularly when they are in our immediate environment. The health of our ecosystem is quantified by the health of the individuals found within it. Racism as a toxic pollutant to our ecosystem on an individual, human-to-human level looks like violence, racial slurs and discriminatory practices that cause harm for no reason other than a person showing up with less or more melanin (skin pigmentation) than another person.

Education, health, economic, and civic success for residents are best achieved when systems and services intended to address these areas are co-ordinated. When schools and neighborhoods are connected to critical city- and community-based services and private health, education, and economic assets, then residents are better able to access important wraparound services that support their well-being.

***

Cities and towns, which we call community, must be at the forefront of spurring policy, systems, and environmental changes that seek to remove structural, institutional, and social barriers to success.

Citizen involvement is critical at the onset of any planning. Robust civic engagement is another essential part of thriving communities where residents have equitable opportunities for achieving knowledge, health, and wealth.

When residents are engaged and are a respected part of their community’s decision-making processes, they are better able to convey their expectations and needs and have these demands met through normal democratic channels. When residents are disempowered or do not perceive avenues for engagement, then their frustrations and pent-up demands get expressed outside of regular channels.

It is our responsibility to identify how racism has permeated our reality and develop remedies to correct it. Creating community justice is one such way.

Thriving, inclusive communities understand the role of interdependence and value the engagement of all residents. This represents a win for the well-being of individuals and the well-being of the places in which they reside.

The most important component is the desire to do so. Our society is hungry for truth. Embodying what our whole body well-being is in its truest sense gets us closer to functioning with community justice.